Preached Sunday, March 2, 2014 at the Church of the Holy Trinity on Manhattan's Upper East Side. Scripture texts that this sermon is based on can be found by clicking here.

Today is the last Sunday of Epiphany – this Wednesday is Ash Wednesday, and we begin our weeks-long journey thought Lent. The passage we read this morning is always the account of the Transfiguration of Christ on the mountaintop.

The Transfiguration appears in Matthew, Mark and Luke, and it comes just after Jesus has predicted his own passion and suffering. Peter was so shocked to hear Jesus’ predictions of his crucifixion that his response was a memorable one. “God forbid!” Peter exclaimed, to which Jesus offers his famous rebuke, “Get behind me, Satan.” Jesus is aware that what is coming for him, his suffering and death, which is also what is coming for us in the culmination of Lent at Holy Week, what is coming is going to be hard on his followers, the very idea of it is too hard for Peter even to contemplate.

In our account from Matthew’s Gospel, we find a transfigured Jesus accompanied by two major figures from the history of the Hebrew people. There on one side of Jesus is Moses. Of course, Moses is a great hero of Salvation history. Moses parted the Red Sea and brought the children of Israel out of captivity, he fed them manna from heaven in the desert and led them to the Promised Land. It was through Moses that God gave the law to the people of Israel, detailing for the first time in human history how a people of God would relate and interact with their God and with one another; in a reflection of God’s love for them.

In Jesus’s day, many expected Elijah’s return, which they believed would herald the imminent coming of the Messiah. The gospels speak of John the Baptist as Elijah come to herald the Messiah’s arrival. Elijah healed the leper Naaman, and raised the son of the faithful widow. And of course, it is Elijah who goes up on a mountaintop like Moses, and encounters the living God, not in the earthquake or the mighty wind, but in the still, small voice.

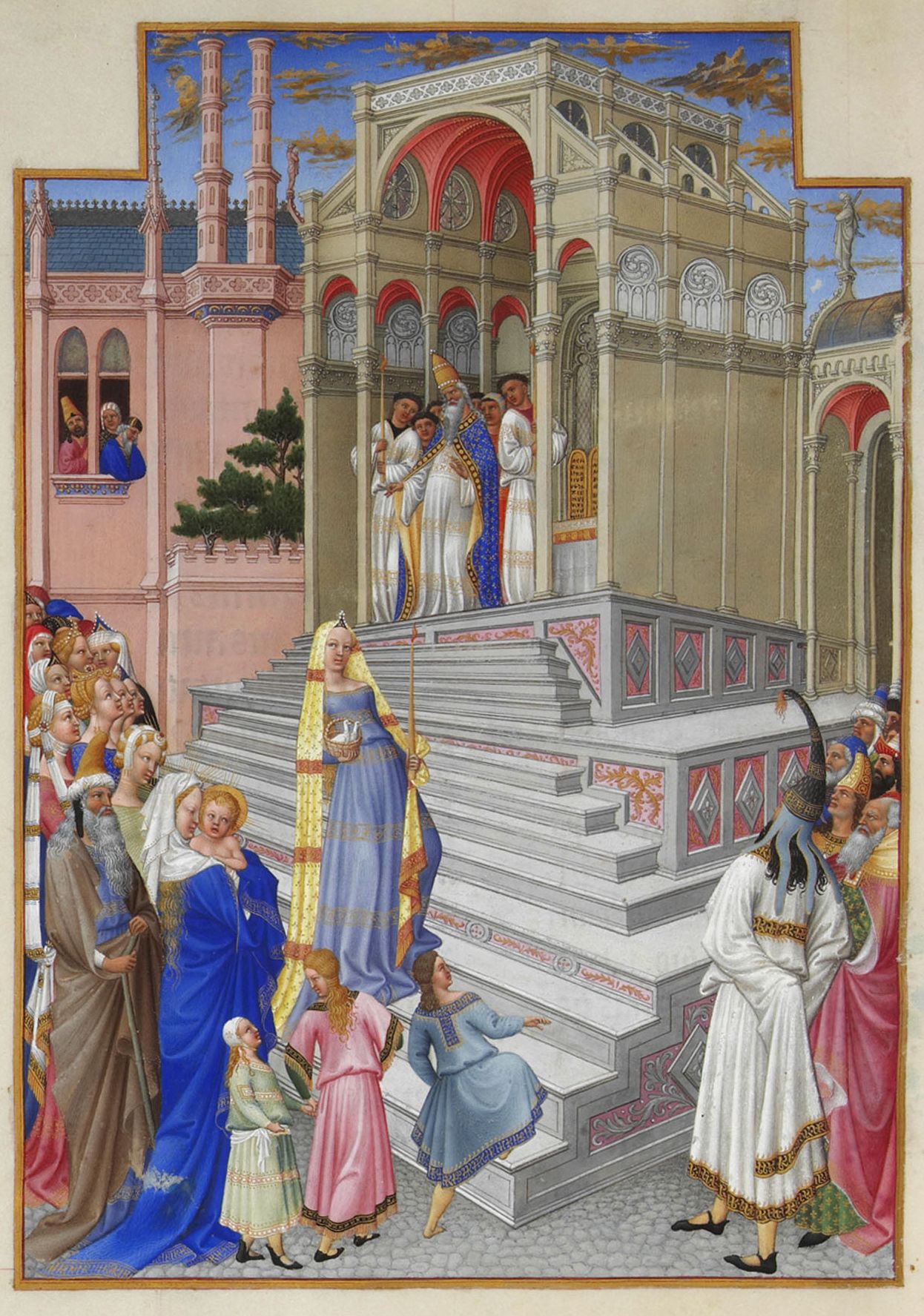

In first century Judaism, it was widely believed that Moses and Elijah were taken to the very presence of God at the end of their lives and resided with God in the heavenly habitations. So it’s not surprising that they should appear with Jesus when Jesus puts on the glowing countenance of a heavenly being. But what’s important about these two figures in the context of the Transfiguration is that they testify to Jesus, to his place in Salvation history, to his coming glorification. Both the law and the prophets, in the persons of Moses, giver of the law, and Elijah, progenitor of the prophets, stand as witnesses to Jesus’ glorification on the mountain. Jesus stands as their more than worthy successor, having shown his authority over the sea and his ability to feed the many -- like Moses, and having cleansed the leper and raised the dead, as did Elijah. And as at his baptism, the voice from above – speaking the exact same words -- proclaims to us all that this transfigured Jesus is the very Son of God.

Transfiguration is at the heart of our faith, it is at the core of what it means to be a Christian. We are the heirs of the people who walked to freedom on dry land in the midst of a transfigured great sea. It was to a daughter of these ancestors in faith that a miraculous message was brought by an angel, and she too was unexpectedly transfigured, made great with child though yet a virgin. And it was her child who became the miracle worker who was able to transfigure water into wine, to heal the sick, to quite the minds of those pestered by demons, to conquer death. This carpenter’s son, this synagogue loudmouth, this rabble-rouser, was revealed to be none other than the Christ, the anointed one, the Son of God. This lowly Galilean, from a forgotten backwater of the Roman Empire, who suffered the most ignominious of deaths, nailed to a tree by the side of the road out of town, left to die in the noonday sun. This broken, lifeless body laid to rest in a borrowed tomb that would be transfigured into our resurrected Lord. This Jesus whose transfiguration was not his alone, but who, through his own death and resurrection has transfigured our humanity and made us little lower than the angels, transfiguring our mortal life into everlasting life in him.

++++++++++++++++++

But you might have guessed the verse, the phrase, the few words in this passage that are my favorite. I usually repeat them at announcement time when I thank you all for coming. They are Peter’s words, spoken in the midst of his awe at the vision of the ancient prophets and the transfigured Jesus before him. He says, rather simply, “It is good that we should be here.”

I can’t know why you came here this morning, what you are seeking, or what you’re seeking refuge from. But nonetheless, it is good that we should be here.

Maybe you came here today to experience some of this transfiguration. Maybe you hope to be transformed here. Or maybe you came here to escape transformations. Maybe you’re here to find something solid to cling to, in a world that seems to be transfiguring and transforming itself daily, if not hourly. Maybe it’s a bit of both. In either case, it is good that you should be here.

It is good that we should be here, just to be here, to spend time here. Really, what else would you be doing with this hour or so? Spend the time here. You may hear something read, or preached or said or sung that will resonate within you, kicking off your transformation and your own transfiguration. I hope so. But if not, it matters not; it is good that you should be here. The more often you are here, the more likely that morning when something here, someone or something, will spark your transformation.

I’m using those two words interchangeably – transfiguration and transformation – and really, I probably shouldn’t. Transformation is about change, usually. But, for Jesus at least, transfiguration is not about change so much, as it is about revelation. Jesus is revealed to be the successor to Moses and Elijah, he is revealed to be both a heavenly being as well as a human being; he appears to be and is called the Son of the Living God.

At his Transfiguration, Jesus doesn’t become something else, rather he becomes his true self, his essential self; and his essential reality is revealed. That can be what happens to you too, in this place. For here we come to believe that the truth about us, our true selves, our authentic selves, is that regardless of who we are in the world, here, we are none other than the beloved children of a loving God.

Divorced, over-weight, out of work, broke, brokenhearted, neurotic – and blessed and oh, so highly favored children of the Almighty God.

It is good that we should be here, to give worship and praise to the awesome God who grants unto us salvation, and eternal life, and the glories of heaven. It is good that we should be here, to witness the transfigurations around us, as we journey together, through life, with its victories and losses. It is good that we should love each other here, for in that, we become a more perfect reflection of the God who created us in the divine image, and who loves us so. It is good that we should be here to offer ourselves, our bodies and our lives, to be transformed and transfigured by service, and worship, and community membership, into good and faithful servants of God, of each other, and of God’s beloved poor.

It is good that we should be here. We might not be transformed or transfigured today, or even tomorrow. But we might be the one smile that breaks through the loneliness of our pew mate. We might offer the first true word of welcome to a wounded Christian who has not found welcome in her church community. We might see the transfiguration of one of our elderly fellow worshippers, as old age begins to take its toll, and this might be the day we offer to walk them home, maybe share some brunch and hear the story of their faith, before they are gone from among us, bound for the glory that awaits.

Or maybe we’ll not hear, or see, or feel anything particularly worthy this morning. And we’ll go home wondering why we bother. And then maybe we’ll come to realize that most things leave us feeling this way, and we’ll finally realize that it is our resistance that keeps joy at bay, and we’ll begin to tear down those walls of resistance, and come more fully into relationship with our community and with our God.

In any case, in every case, for whatever reason or for none, for the first time or the last, carrying a heart full of joy, or sorrow, with great expectations or seething with resentment, no matter why, or from where you come, or what you seek or seek to avoid here; it is good that we should be here. Very good, indeed, that we should be here, together in the presence of the living God, and in the sacred company of one another. Amen+

© The Rev. Mark R. Collins