There was an interesting story in the New York Times on Thursday. St. Peter’s Catholic Church in lower Manhattan is celebrating its 225th anniversary. It is the oldest Roman Catholic church in New York State. Its cornerstone was laid in 1785, not long after the end of the Revolutionary War when the newly formed United States had not yet begun to write its Constitution and ensconce within that Constitution, our Bill of Rights.

There were only 200 Roman Catholics in New York at the time, just a few more than usually worship here on Sunday mornings, and most of them quite poor. But if St. Peter’s long tenure is something to celebrate today, it was certainly not seen as something worth celebrating at its inception. Protestant New Yorkers at the time viewed the new Roman Catholic presence with suspicion. As the Times put it,

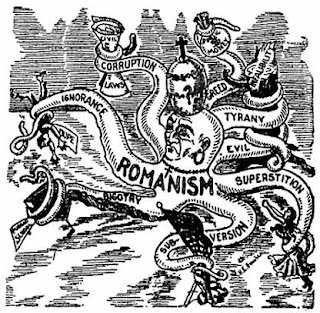

“Many New Yorkers were suspicious of the newcomers’ plans to build a house of worship in Manhattan. Some feared the project was being underwritten by foreigners. Others said the strangers’ beliefs were incompatible with democratic principles. Concerned residents staged demonstrations, some of which turned bitter.”Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Even after two decades, the people of St. Peter’s were still facing the wrath of their fellow Christians. This is from the Times once again:

“On Christmas Eve 1806... the building was surrounded by Protestants incensed at a celebration going on inside — a religious observance then viewed by some in the United States as an exercise in “popish superstition,” more commonly referred to as Christmas. Protesters tried to disrupt the service.In the melee that ensued, dozens were injured, and a policeman was killed.”

I dare say, those of you who join us this Christmas Eve will be “incensed” as well, but in somewhat different manner, probably in a manner quite similar to what was going on at St. Peter’s on Christmas Eve 1806.

I dare say, those of you who join us this Christmas Eve will be “incensed” as well, but in somewhat different manner, probably in a manner quite similar to what was going on at St. Peter’s on Christmas Eve 1806. Strange customs from foreign lands, strange people with foreign ways, strange beliefs that may or may not be compatible with our own.

New Yorkers didn’t like such things in 1785 when St. Peter’s Catholic Church was being built -- and some Americans -- though I suspect not many of them New Yorkers -- don’t like it today when the Islamic Cultural Center planned for downtown Manhattan is discussed.

And people didn’t like foreigners in Ruth and Naomi’s time either. Our Old Testament reading today tells the familiar story. Years ago, Naomi and her family left their hometown of Bethlehem and fled to Moab in a time of famine. They settle there, raise two sons, and those sons marry two Moabite women.

And people didn’t like foreigners in Ruth and Naomi’s time either. Our Old Testament reading today tells the familiar story. Years ago, Naomi and her family left their hometown of Bethlehem and fled to Moab in a time of famine. They settle there, raise two sons, and those sons marry two Moabite women.The family knows hardship when Naomi’s husband and her sons die. Then famine comes to Moab, and Naomi and her daughters-in-law Orpah and Ruth must rely on their own resources to survive.

Naomi hears that in her hometown of Bethlehem, there is plenty has return, so she readies herself to go home. And as she goes, she tries to send her daughters-in-law back; she tells them to return to their mothers’ houses and to find new husbands. Naomi wants her daughters-in-law to be happy again, to know love and security and fulfillment, rather than to be shackled to her and her family’s bad luck and poor fortunes. Orpah returns to Moab, but Ruth refuses to do so. Ruth tells Naomi that she is not going back.

In verse 16, Ruth says to her mother-in-law, “Your people will be my people, and your God will be my God.” But in fact, the original Hebrew has it a bit differently. There are no verbs in that phrase in the Hebrew Bible, and the verse can be read literally as “Your people, my people; your God, my God.” It’s a statement of what is, not what will be. Ruth is telling Naomi, “I can’t turn back, and I can’t turn my back on you, because we are a family -- your people are my people, your God is my God -- and that means we stick together, no matter what.”

Later in the story, Naomi and Ruth’s fortunes take a turn for the better. Ruth the Moabite marries Boaz, Naomi’s kinsmen, and she becomes the forebear of Israel’s greatest hero, David.

But not everyone in Israel was happy about people like Ruth the Moabite. The prophets Ezra and Nehemiah in particular urged the Israelites to abandon the foreign wives they had taken up during the time of the Babylonian captivity, they wanted to purify Israel, so that the calamity of the Babylonian captivity would never come to pass again.

That sounds familiar too, doesn’t it? Purify the nation so that we aren’t visited with another calamity like September 11th.

One biblical scholar suggests that the story of Ruth is in fact a subversive parable, meant to counter the xenophobia of Ezra and Nehemiah. For Ruth the Moabite becomes the matriarch of the House of David, Israel’s greatest king, and the ancestor of our savior Jesus of Nazareth.

Perhaps the foreigner in our midst doesn’t make us weaker, more vulnerable, perhaps the foreigner makes us better, stronger, safer. Like the Samaritan in our gospel story today, it may be that the outsider, the one we see as our religious rival or our foe might have something to teach us.

Maybe there is something we can learn about faithfulness from such a one as Ruth the Moabite. Maybe there is something we can learn about how to give thanks to God from those we would treat as despised Samaritans in our own day.

+++++++++++++++++++++++

Can you imagine a time when celebrating Christmas in church was viewed as something foreign and suspicious by American Christians?

The Rev. Kevin Madigan, the pastor of St. Peter’s Catholic Church wrote to his parishioners this past summer saying,

“We were treated as second-class citizens; we were viewed with suspicion… Many of the charges being leveled at Muslim-Americans today are the same as those once leveled at our forebears.”

We may have our differences, but most of us would look upon our Roman Catholic neighbors as “our people,” and we would certainly see their God as our God.

Maybe someday, the same will be true for our Muslim brothers and sisters, and maybe someday, we’ll stop wrangling as our Epistle tells us to do and we’ll see that all the children of Abraham -- Jews, Muslims and Christians -- are one people, and that we all worship the God who is One, even if we have very different understandings of that God, and even if we worship the One God in very different ways.

Then, on that day, we can all sing the words of our psalm, in a beautiful harmony, and really mean them:

“Praised be the name of the Lord,

high over all the nations, the Lord,

over the heavens His glory.”

high over all the nations, the Lord,

over the heavens His glory.”

(Ps 113: 3-4)

Amen+

© The Rev. Mark R. Collins

No comments:

Post a Comment