In the neighborhood where I grew up, at the end of the street, right next to our house, there was a field. It was probably about an acre or two in size. It was rarely mown; it stood in tall green grass for most of the summer which turned wheaten in the winter months when it was often covered in white frost. In the middle of the field, a generation or two of children armed with spoons, sticks and the occasional shovel had dug a hole down to the vast depth of about a foot and a half. As is always the case with children, the field was a big canvas onto which we painted our playtime fantasies.

It was a time when Combat starring Vic Morrow and directed by Robert Altman was popular on TV as was The Rifleman starring Chuck Conners. So the games of

choice in our neighborhood were either Army – or Cowboys and Indians. Our field might then serve as the wide open west, and pitched battles between settlers and savage Sioux warriors would be waged on a Saturday afternoon -- in which case, the hole served as the all precious fort that must be defended at all costs, and that would inevitably be surrounded at some point in the battle, allowing some overdramatic kid to shout, ‘We’re completely surrounded by Indians!” with a blood-curdled terror that would only add to everyone’s enjoyment. At other times, the field would serve as the snowbound Russian Front, and the Allies would battle the Nazis from the cover of their front line foxhole, lobbing dirt clod hand grenades with a merciless accuracy.

choice in our neighborhood were either Army – or Cowboys and Indians. Our field might then serve as the wide open west, and pitched battles between settlers and savage Sioux warriors would be waged on a Saturday afternoon -- in which case, the hole served as the all precious fort that must be defended at all costs, and that would inevitably be surrounded at some point in the battle, allowing some overdramatic kid to shout, ‘We’re completely surrounded by Indians!” with a blood-curdled terror that would only add to everyone’s enjoyment. At other times, the field would serve as the snowbound Russian Front, and the Allies would battle the Nazis from the cover of their front line foxhole, lobbing dirt clod hand grenades with a merciless accuracy.

Most of the kids on our block were my little brother’s age, which is 19 months younger than me. Now 19 months is not a big age difference, but when you’re only 60 or 72 months old, it can seem like an eternity. Being so much older by the vast stretch of 19 months, and being therefore much more sophisticated, I eschewed both Army and Cowboys and Indians.

Somewhere in our family set of World Book encyclopedias, I had seen an entry all about medieval castles. I wanted to play Kings and Castles, not Army or Cowboys and Indians. I would lobby fiercely on behalf of my fantasy, but I rarely won out. No one really knew the script of Kings and Castles. Vic Morrow and Chuck Conners hadn’t supplied us with our lines. On the rare occasion when everyone agreed to play Kings and Castles, we’d run out of plot lines and scenarios rather quickly and then someone would shout, ‘We’re surrounded by Indians!’ and the battle would morph into Cowboys and Indians – and I’d sulk off home to read more of the encyclopedia.

For most of human history, our ideas about monarchy and our ideas of divinity have been closely linked. The Roman emperors were proclaimed Gods or Sons of Gods. And the divine right of monarchs, the belief that the right to rule was granted to kings by God himself was an idea that was very closely held throughout European history, perhaps by no one more staunchly than James the First of England, the same King James we have to thank for the “King James” Bible.

In fact, the posture we use to pray to God is derived from the posture of supplicants and liegemen in obeisance before medieval kings. Often when we pray, we kneel, as did our medieval counterparts before their king, and we place our hands like so, as they did before the king to make a pledge of allegiance to their sovereign.

In fact, the posture we use to pray to God is derived from the posture of supplicants and liegemen in obeisance before medieval kings. Often when we pray, we kneel, as did our medieval counterparts before their king, and we place our hands like so, as they did before the king to make a pledge of allegiance to their sovereign.

So, there’s been a sort of cross-polination between our secular ideas about royalty and kings, and our sacred ideas about God – and about Jesus in particular. Christ is king of heaven and earth, we say, and sometimes sing. And it is Christ’s kingship of earth that is the focus of the celebration of Christ the King Sunday. This commemoration of Christ’s kingship wasn’t added to the liturgical calendar until 1925. World War I, which had been for most of Europe a devastating, soul-killing and faith-destroying event was just ended. Christian nation had waged war against Christian nation, with a ferocity and deadliness that only modern technology could have brought about. A few of the old monarchies gave way in the aftermath of the war to either democracy – which owed its sovereignty to the consent of the governed, not the divine right of the king, or to Communism, which was officially an atheistic form of governance.

The church sought to help restore order and peace (and maybe to restore a bit of its own prestige) by reminding the war-ravaged nations of the world that Christ was indeed king of earth as well as heaven, and that we should govern each other, and live together, as if continually in his sight, and under his authority. As today’s gospel reading from Matthew puts it, “(H)e will sit on the throne of his glory (and) all the nations will be gathered before him.”

But what sort of king would Jesus be if instead of a cross he had ascended an earthly throne like those in Westminster Abbey or in the Imperial Palace in Tokyo? We get a pretty clear picture from today’s gospel. In our reading from Matthew, we see Jesus acting in one of the principle roles of an earthly king -- that of judge. The courts of earthly Kings, literally where one came to ‘court’ the favor of the king, were places in which suits and trials took place. The king’s court became our law court, where a judge – or sometimes a jury -- takes the place of a king, in judging between truth and falsehood, innocence and guilt.

Usually, one’s standing in the court of a king is directly related to one’s relationship to that king. Being a subject of the king meant complete subjugation to that king. Being a liegeman meant supplying soldiers, arms and most certainly money to the king. The chief crime against a king is treason. To be disloyal, or disobedient, or to threaten or usurp the power of a king was and often still is the capital crime.

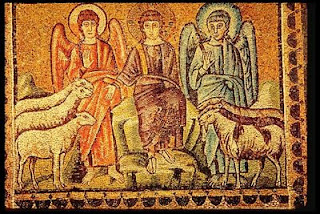

The sheep in today’s gospel fully expect this type of arrangement between themselves and the Son of Man seated upon his throne. Jesus tells them that they have earned the king’s favor by acting with charity, mercy and generosity towards him. But the sheep are a bit confused. They’ve never seen the Son of Man or paid homage before his throne. They’ve never fed him, or clothed him…They’ve never been aware that they have been at his service in the ways in which he describes. And here when we see Christ the King acting as king -- it doesn’t bear much of a resemblance to kings and rulers we know from history or from experience. In Jesus’ account, the Son of Man tells the sheep, it is not to me directly that you have shown such goodness, but rather it is to the least among you, the poor, the hungry, the thirsty, the sick, the imprisoned, the homeless. It is when you when you treated them with mercy and understanding, with charity and goodness, with acceptance and support, you did so to me as well.

The sheep in today’s gospel fully expect this type of arrangement between themselves and the Son of Man seated upon his throne. Jesus tells them that they have earned the king’s favor by acting with charity, mercy and generosity towards him. But the sheep are a bit confused. They’ve never seen the Son of Man or paid homage before his throne. They’ve never fed him, or clothed him…They’ve never been aware that they have been at his service in the ways in which he describes. And here when we see Christ the King acting as king -- it doesn’t bear much of a resemblance to kings and rulers we know from history or from experience. In Jesus’ account, the Son of Man tells the sheep, it is not to me directly that you have shown such goodness, but rather it is to the least among you, the poor, the hungry, the thirsty, the sick, the imprisoned, the homeless. It is when you when you treated them with mercy and understanding, with charity and goodness, with acceptance and support, you did so to me as well.

Here is a king who is not a member of a dynasty or an aristocracy. Here is a king who is one with the least of women and men. It is not in paying court to the king that we are granted the king’s favor, but in paying attention to the ones that are most often forgotten and overlooked. The reward comes from this king not from courting power, but in empowering the powerless.

Once again, at the core of our Christian faith is a paradox: a king who does not need us to honor and worship him in his glory, but one that asks that we honor and glorify him in serving those most in need. To gain the favor and the good opinion of the one at the top of the cosmic order, we need look not up to the skies, but rather down, toward the lowliest among us, and offer them all that we might offer our King and Savior were he here in our midst.

What is so revolutionary about this particular passage from Matthew is what is missing from it. In it there is no requirement to believe in… well, in anything really. There is no profession of faith, there is no ancient law code to adhere to, no baptism or other initiatory rite to undergo, neither Jerusalem nor Rome nor Canterbury is said to be the seat of authority. There is no call for repentance or renunciation of vices or repudiation of other gods or religions.

Based on this passage alone, salvation appears to be something of a two-way street. We will be saved in as much as we seek to save those in need and peril around us. We will be fed at the heavenly banquet if we seek to feed the hungry. We will drink of the springs of eternal salvation if we seek to quench the thirst of the parched. We will be visited with honor and glor when we visit the sick and the shut-in and the imprisoned. We will live in splendor in the heavenly mansions if we work to house those whose best hope of shelter is but a cardboard box or a tattered tent.

It is these saving acts that will guarantee our eternal salvation in heaven. Nothing more -- and nothing less.

What a world it would be if Christ was indeed our king, or if we acting like he was. No more games of Army or Cowboys and Indians on the deadly scale that the last century saw and we still see in this century. No more games of Kings and Castles that grant more power and riches to the already powerful and rich. A world in which the lowly are lifted up and we, by and through our regard for the lowly, are redeemed along with them. A kingdom of Christ on this earth that might bear some slight resemblance to the heavenly kingdom he has gone to prepare for all who act with mercy, charity and justice.

What a world it would be if Christ was indeed our king, or if we acting like he was. No more games of Army or Cowboys and Indians on the deadly scale that the last century saw and we still see in this century. No more games of Kings and Castles that grant more power and riches to the already powerful and rich. A world in which the lowly are lifted up and we, by and through our regard for the lowly, are redeemed along with them. A kingdom of Christ on this earth that might bear some slight resemblance to the heavenly kingdom he has gone to prepare for all who act with mercy, charity and justice.

Would that Christ were truly our King and we his most loyal subjects who sought his favor by honoring and worshipping him just as he asks us toin compassion for, generosity towards, and solidarity with the least among us. Amen +.

© The Rev. Mark Robin Collins

Coffee Hour Critique: At coffee hour, one of my parishioners pointed out that this sermon sounds like it posits a theology of works righteousness -- that we are justified by our good works, and not by faith alone, as Martin Luther, and the Reformers would have it. I think she’s got a very good point.

I was hoping to make the point -- without using the theological jargon -- that this passage makes a good case for Christian Universalism which is the view that Christ died to redeem the whole world, inclusive of those of other faiths and beliefs who live righteously. But in courting one theological tenet I ran afoul of another.

To be clear, I believe that we are justified by faith alone, and that our righteous works are an expression of that justification. Salvation is a free gift of God that we can in no way earn for ourselves. No matter what Jesus says in Matthew 25:31-46... (wink)

1 comment:

Good postt

Post a Comment